On the doorposts of every Observant-Jewish home, you will find a little rectangular case. Inside that case is a Mezuzah. It’s there because the Torah commands us to affix a Mezuzah on each doorpost in our homes.

What is a Mezuzah? In brief, a Mezuzah is two chapters from the Torah written (in Hebrew, of course) on a piece of parchment. The parchment is then rolled into a scroll, wrapped in paper or plastic, usually inserted into a hard-plastic or metal case, and affixed to the doorpost. We will, with Hashem’s help, discuss this more at length below. First let us discuss the meaning of this Mitzvah.

The essence of the mitzvah of Mezuzah is the concept of the Oneness of G-d. The very first verse written on the Mezuzah is the Shema: “Hear oh Israel, the L-rd is our G-d, the L-rd is One.” When we pass a doorpost, we touch the Mezuzah and remember that G-d is One: a Oneness that is perfect and unique, a Oneness that is not one of many, nor one of a species. G-d is One without parts, partners, copies, or any divisions whatsoever.

Moreover, Hashem is our G-d, Whom we must love and obey, and Who protects us.

Every moment that the Mezuzah is on your doorpost is another merit in your favor, even though you are not actively doing anything!

How a Mezuzah is Made

There is a common tendency to call the box the “Mezuzah,” and the scroll the “parchment.” This is a mistake. The Mezuzah is the parchment scroll with the writing on it. The box is just a box. It’s primary purpose is to protect the Mezuzah that is inside it.

A Mezuzah must be handwritten. If it is printed, copied, photographed, or produced by any means other than writing, then it is invalid and may not be used.

A Mezuzah must contain in Hebrew, in a special alphabet, the following two chapters: Deuteronomy 6:4-9, and Deuteronomy 11:13-21. Anything else, or anything more or less is completely unacceptable. There is only one way to write a Mezuzah. There are no alternatives.

After the Mezuzah is written, it should look something like this:

(Please note that all the Names of Hashem in the gif to the left have been intentionally created incomplete, to prevent any accidental desecration. However, it is still Torah, and should not be treated lightly.)

(Please note that all the Names of Hashem in the gif to the left have been intentionally created incomplete, to prevent any accidental desecration. However, it is still Torah, and should not be treated lightly.)

This is not necessarily the actual size. A Mezuzah can be anywhere from two inches square to six inches square. However, it is inadvisable to use a two-inch square Mezuzah, as they are harder to write, and therefore more prone to errors and spoilage.

There is also writing on the outside of the Mezuzah, including other Names of Hashem, one of which becomes at least partly visible when the Mezuzah is rolled.

Of course, the Mezuzah will not look like this on the doorpost, because Jewish Law says that it must be rolled and placed in a case.

The Mezuzah must be written on special, handmade parchment. If it is written on any other type of surface, it is invalid. The parchment must come from a kosher animal, such as a cow, or a goat, and must be prepared by means of specific processes.

The ink used in the writing must also be made according to specific Laws. Among other things, it must be black. The quill used for the writing is also made a certain way (but that’s mostly for practical reasons, not for legal reasons). And the writing of the Mezuzah itself must be performed according to many very exacting Laws.

While the creation of a Mezuzah, tefillin, or Torah Scroll takes a great deal of work, that’s not where the biggest effort goes. The most work must be put into the fashioning of the person who writes the Mezuzah! And the person who writes the Mezuzah is the only one who can do that work for him.

The person who writes the Mezuzah is called a sofer (scribe). Since Mezuzah is a Commandment of the Torah, we must put the maximum holiness into it. This can be done only when a holy person writes the Mezuzah. A sofer must be fully trained in all the many Laws of writing mezuzos, tefillin, and Torah Scrolls. He must also love and fear Hashem, and be very punctilious in performing the Commandments properly and with holiness.

In the case of Mezuzah and tefillin, there is also an added concern that demands that the sofer be concerned about performing the Commandments properly. When a Mezuzah is created, the sofer must write the words in order. If even one letter is written out of order, the entire Mezuzah is invalid. If he writes an entire Mezuzah, and then discovers that one letter was written completely incorrectly, he cannot fix it out of order. If he fixes the letter, he then has to erase and rewrite the entire Mezuzah from that point forward. The problem with this is that often this means that he would have to erase Hashem’s Name, and that is forbidden.

So, if he makes a mistake with, say the third letter in the Mezuzah, and he discovers it only later, or if the third letter got ruined later somehow (like ink or water fell on it), this is a problem. He has to rewrite the letter, but that means that he has to erase and rewrite every letter — in order — from the third letter until the end. However, the third word of every Mezuzah is Hashem’s Name, and none of the letters in Hashem’s Name may be erased. (It is forbidden to erase even one letter of Hashem’s Name.) This means that the entire Mezuzah is invalid, because one letter is invalid, and the Mezuzah must now be put away, according to the Laws of invalid holy items. (The Law of writing entirely in order is true for Tefillin as well, but not for Torah Scrolls.)

This means that if a sofer is unscrupulous, and he finds an error, he might fix the Mezuzah improperly, and the unsuspecting consumer now has an invalid Mezuzah, and is not fulfilling the Commandment! What is he to do about that?

This is why we must purchase our mezuzos only from Hashem-fearing Jews.

But there is an even worse scenario. The Law states that if a man does not believe in Hashem, or even if he does not believe in just one word of the Torah, and he writes a Mezuzah, or Tefillin, or Torah Scroll, even if he keeps all the Laws properly, his writing is invalid, and what he has written must be buried. If he denies even one word of the Torah, his works are not holy, and they may not be used at all, but must be buried. (This is not a far-fetched scenario at all. There have been and there are today many non-religious Jews in this field.) So we must be very careful from who we buy our mezuzos, tefillin, and Torah Scrolls.

Unfortunately, in the course of my work in this area (and you will hear the same from anyone who has ever worked in this field), I have found many mezuzos that were never properly written, and were definite frauds. I once opened up a Mezuzah case and found inside a piece of paper with the Ten Commandments in English! I have found printed mezuzos, mezuzos on paper, scrawled mezuzos, and any number of fraudulent things. Many people would never have been able to tell that these were fakes. We must be very careful from who we buy our holy items!

In the writing of a Mezuzah, tefillin, or Torah Scroll, there are also many Laws concerning the shapes of the letters. Calligraphy really makes a difference here! If a letter is misshapen, the entire Mezuzah, tefillin, or Torah Scroll is invalid. Yes, an entire Torah Scroll is invalid because of one misshapen letter. And the shape of each letter is intricately and precisely described by Jewish Law. It is not up to the individual sofer to decide how a letter should look.

However, within the limits of the Law, there is a lot of leeway. In general, the better the handwriting, the nicer the Mezuzah. Jewish Law considers nicer Mezuzos better, because they enhance the Mitzvah. Since they are harder to write, they usually cost more. Buying a more expensive Mitzvah is an expression of love for Hashem’s Commandments. It doesn’t mean that Hashem cares how much money you spend. Hashem cares how you feel when you decide to buy a nicer Mezuzah.

However, you are not at all required to spend more than you can afford for a nicer Mezuzah. You are required to pay more than you can afford — even all your money — if that’s what it will take to get kosher Mezuzos for your home. But if you are spending your last dollar to buy Mezuzos, then you should probably get cheaper Mezuzos.

There are not many Laws concerning the case in which the Mezuzah is put. It doesn’t matter who made the case. It could even be made by a Gentile. As long the Mezuzah fits in without being squashed or folded, it should be okay. Unfortunately, there are manufacturers of Mezuzah cases who have no idea of how a Mezuzah looks, and sometimes mezuzos can’t actually fit into those cases! So take care before buying a Mezuzah case to make sure that the Mezuzah can actually fit inside.

I also must point out that Mezuzos can actually lose quality over time. Even a kosher Mezuzah that was in excellent condition and quality when created can spoil over time. For example, when a Mezuzah gets old, it often starts to dry up. Cracks often develop in the letters, which invalidates it. I once opened a very old Mezuzah, and one of the letters popped off the parchment and hit me in the face!

Letters can also fade, and thereby invalidate the Mezuzah or tefillin. Sometimes a slightly faded letter can be rewritten, but only a properly trained sofer knows when, so we must always bring it to a sofer to be checked.

Jewish Law states that a Mezuzah must be checked about once in every three or four years.

The Requirement of Mezuzah

Any Jew, man or woman, who lives in an apartment or house is required to place Mezuzos on the doorposts of his or her home. It is not the obligation of the landlord or landlady. It is the obligation of the person living there.

It is best to place the mezuzos on the doorposts when you first move in. In any case, do not wait longer than thirty days before putting up the mezuzos.

If you will not be living in that home for longer than 29 days, you are not required to have Mezuzos.

Generally, Jewish Law defines a door as having a ceiling and two doorposts. To be a doorway, it must have a lintel. A lintel is a horizontal top-piece over the doorway, which gives the opening the look of a doorway. An opening (like a gate) that has no ceiling, but just has two vertical posts, does not need a Mezuzah. Since there are many types of doorframes, it is best to describe to the sofer who sells you your mezuzos any different type of doorways you may have; he should be able to tell you which ones need mezuzos and which do not.

The corner of a hallway usually counts as a doorpost. Again, ask your sofer.

Every room or closet that is about 36 square feet or more needs a Mezuzah on the door.

The doorway to a small room or hallway that leads to a larger room, or leads to a staircase, needs a Mezuzah.

Every room needs a Mezuzah except for bathrooms. A bedroom and a laundry room needs a Mezuzah.

A gate (that has a lintel) that reaches 30 inches or more higher than the ground must have a Mezuzah.

How to Affix a Mezuzah.

Do not roll the Mezuzah yourself. The sofer who sells it to you should have rolled it and placed it in a case before giving it to you.

The case must be firmly affixed to the doorpost, in a manner that will not easily allow it to fall off. If this is a metal case, to be fixed to a metal doorpost, double-sided tape is strong enough to be used. However, scotch tape should NEVER be used, because it is not strong enough, and making the blessing would be very questionable. The blessing translates, more or less, as “and Who has commanded us to strongly affix a Mezuzah.” So in order to make the blessing before putting up the Mezuzah, we must be sure that we are putting it up strongly. Therefore, the best thing to use is nails. Mezuzah cases usually have nail holes.

The Mezuzah scroll, in the case, should be placed on the inside of right doorpost as you enter the room.

It should be placed as close as possible to the outside of the doorway, while still remaining within the inside of the doorframe, as in the pictures above. However, if you have one of those doors that swings in both directions, that is, both in and out of the door frame, it will hit the mezuzah. In that case, you should place it on the outside (not the inside) of the door frame as you enter, as close as possible to where the mezuzah is really supposed to be.

The door leading into every room (whether the door to your house or the door to your bedroom, kitchen, etc. – except the ddor to a bathroom or small closet) needs a Mezuzah, unless the door has been boarded up or sealed shut so that it is impossible to use the door as it is. Simply locking the door and never going through is not enough. A door that is not boarded up still needs a Mezuzah, even if it is locked and never used.

The Mezuzah should be placed at the bottom part of the top third of the doorpost. So, for example, if your doorway is 9 feet high (which is rather high, I know, but this is just an example), you would place the Mezuzah at the bottom of the third foot from the top. The bottom end of the Mezuzah would be touching the top of the fourth foot counting from the top.

According to Jewish Law, the doorpost does not need to be measured. You can simply look at it, and place it more or less at the correct spot. The placement does not need to be precise.

The Mezuzah should be placed within the doorframe, underneath the lintel. With doors that swing both ways, it is usually impossible to place a Mezuzah inside the doorframe, as that would impede the door from swinging the other way. In such cases, place the Mezuzah on the outside of the doorframe, as close as possible to the doorway.

Ideally, however, the Mezuzah should be placed within the doorframe, not on the outside of the doorframe, and not on the inside of the room.

The Mezuzah should be placed within the frame (wherever possible), but as close as possible to the outside of the doorframe. This way, one of the first things you meet when you come home is a Mitzvah.

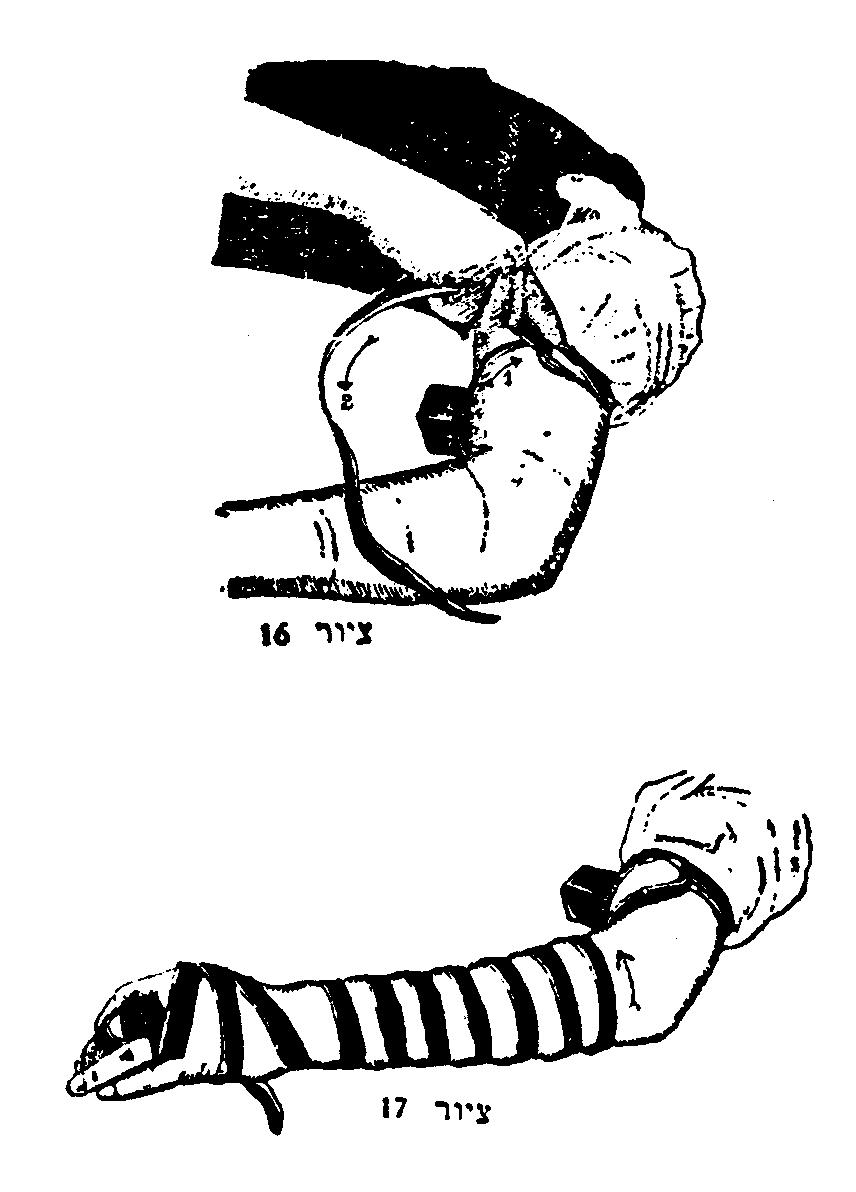

The Ashkenazic custom is to place the Mezuzah at a slight angle (about 45 degrees or less) to the left, with the top facing in to the room. The Sefardic custom is to place the Mezuzah vertically. If you put them up according to the other custom, it is not necessary to fix it. Since Mezuzah scrolls should be checked about every three or so years, you can change the angle when you put them back up.

Never paint over a Mezuzah case. It could ruin the scroll inside, and then you will have no Mezuzah.

On a door onto which it rains, use a waterproof case. This should help protect the Mezuzah inside the case.

Before placing the Mezuzah on the doorpost, hold it in place, with the hammer ready (in the case of double-sided tape, hold it an inch or so away from the doorpost), and recite:

Boruch Attah A-donai E-lohainu Melech ha-olam, asher kiddishanoo bimitzvotav vitzivanoo likvo-ah Mezuzah.

(Blessed are You Hashem our G-d, Who has made us holy through His Commandments and commanded us to strongly affix a Mezuzah.)

Place the Mezuzah on the doorpost and nail it in if using nails.

Make one blessing for all the mezuzos in the house (usually on the front door). After reciting the blessing, do not speak any words at all until affixing all mezuzos throughout the house.

To buy a good Mezuzah, I would suggest you try out a place called Tiferes Judaica.

The Talmud says that a proper Mezuzah offers protection of the home. A king once gave a Rabbi a diamond as a present, so the Rabbi gave the king a Mezuzah as a present. the king did not know what it was, and got insulted. The Rabbi explained, I will have to hire guards to protect my home because of the the gift you gave me, but the gift I gave you will protect your home!

Keeping the Commandments of the Torah always brings blessings, and the Talmud says that keeping the Commandment of Mezuzah brings long life and is a protection for the home. Of course, the holier a home is kept, the more the protection. Therefore we should always be careful of what we bring into our homes. When we are prepared to carry something into our home, whether it be food to eat, or food for thought (books, magazines, etc.), we should stop and consider, whether or not it will shame the Mezuzah to have that carried past it into the home. If we do that, and protect our homes from spiritual invasion, we can be assured that our homes will always be protected from physical invasion.

This is how it should look.

This is how it should look. This is wrong. The shel rosh is too far forward.

This is wrong. The shel rosh is too far forward.

(Please note that all the Names of Hashem in the gif to the left have been intentionally created incomplete, to prevent any accidental desecration. However, it is still Torah, and should not be treated lightly.)

(Please note that all the Names of Hashem in the gif to the left have been intentionally created incomplete, to prevent any accidental desecration. However, it is still Torah, and should not be treated lightly.)